Over the past month, a variety of reports have appeared in the information space regarding the potential establishment of a demilitarized zone (DMZ) on Ukrainian territory. Our author conducted a brief study of historical precedents and presents below some key findings.

What is a DMZ?

A demilitarized zone is an internationally recognized legal regime applied to a specific territory, under which all types and forms of military activity are restricted.

The creation of a DMZ often leads to a range of challenges, affecting not only the territory under demilitarization but also the states that must engage with it. Below are examples of potential risks and threats that Ukraine could face if such a territorial-legal regime is implemented.

1.Risk of Agreement Violations

The most straightforward and easily understood threat is the direct risk of violating established agreements.

A historical example is Hitler’s deployment of troops into the Rhineland demilitarized zone. Germany’s breach of the Treaty of Versailles, coupled with the lack of decisive international response, allowed it to strengthen its position and prepare a foothold for further military action.

A vivid illustration of the international reaction is that European countries labeled this violation of international law as “remilitarization.” Supporting the justification for this assessment, a contemporary British representative, Lord Lothian, commented:

“After all, [the Germans] are only going into their own back garden.”

UCLA Film and Television Archive

Remilitarization of the Rhineland

Remilitarization of the Rhineland

Remilitarization of the Rhineland

Considering the above,if a demilitarized zone were to emerge without proper oversight, Russia could potentially use it as a staging ground to mount a rapid offensive against Ukrainian territory.

2.Control over the DMZ

A key factor in restraining the conflict parties within a demilitarized zone is the presence of a strong and unequivocal force capable of deterring a full-scale attack by a sovereign state.

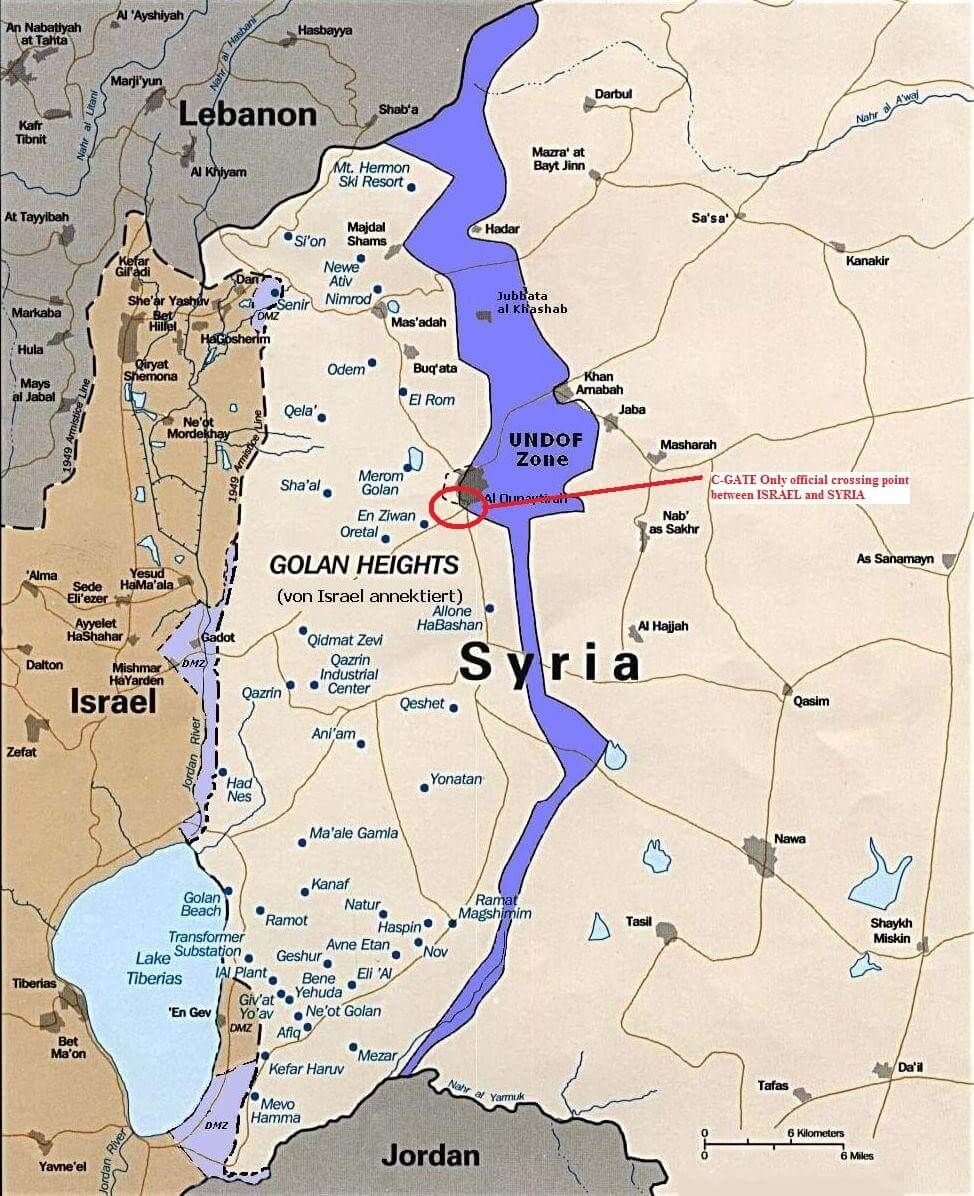

A striking contemporary example is the UN peacekeeping forces’ (The United Nations Disengagement Observer Force) inability to maintain adequate security levels in the Golan Heights.

It remains unclear how the peacekeeping forces proposed for deployment in the demilitarized zone would be composed and how they would respond in the event of renewed Russian aggression. A fully equipped military contingent with appropriate offensive capabilities, armored vehicles, and logistical support could operate effectively—unlike peacekeepers armed only with small arms and traveling in civilian vehicles. There is a critical distinction between actively resisting an aggressor and retreating to Ukrainian-controlled territory for evacuation.

Варто зазначити що Росія також має так звані «Миротворчесике Силы» під виглядом яких вона може здійснювати лобіювання своїх інтересів.

It should also be noted that Russia maintains so-called “peacekeeping forces,” which can serve as a vehicle for advancing its own interests.

**3.International guarantees **

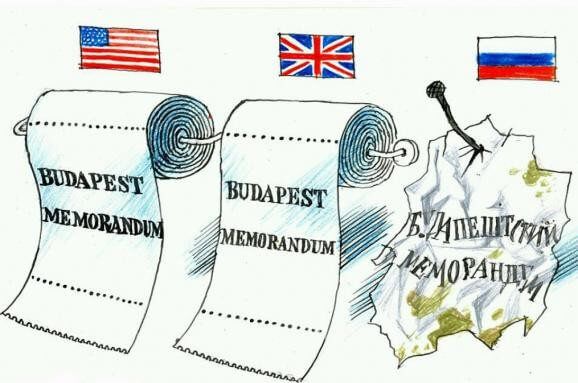

The issue of international guarantees arises as one of the problems that led to proposals for creating a DMZ on Ukrainian territory. Historical experience of one’s own state demonstrates more convincingly than anything else the risks of relying on a potential aggressor to fulfill certain commitments.

The Budapest Memorandum did not provide Ukraine with adequate protection, as the list of security guarantors included, at the time, a potential aggressor. It is highly unlikely that Russia would agree to, or adhere to, agreements in which it would be recognized as the aggressor. Instead, based on the internal and external rhetoric emanating from propaganda sources, one can anticipate a desire on Russia’s part to obtain an equal status with Ukraine, which in turn undermines the likelihood of additional preventive deterrence measures.

Given this context, the Ukrainian state is uniquely aware of the limitations of international guarantees in ensuring security without a proposed and implemented mechanism to guarantee compliance. This represents one of the most critical factors that must be taken into account when making and approving relevant decisions.

4. Implementation challenges

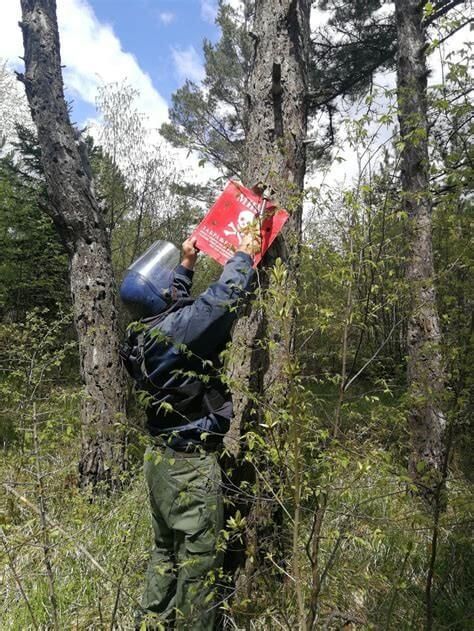

Establishing a demilitarized zone requires substantial technical and human resources, including demining, infrastructure construction, border establishment, temporary checkpoints, monitoring, and more.

The withdrawal of troops is only one of the challenges facing the parties involved in a demilitarized zone._ Implementing the broader set of tasks—such as demining, building infrastructure, establishing borders and temporary checkpoints, and monitoring—requires substantial resources, raising three key questions. First, which party will finance and compensate for damage to local infrastructure. Second, who will carry out these operations directly, given the significant risks involved, particularly in activities such as demining. Third, under whose supervision these processes will take place, as it is essential to have observers monitoring the use of funds and ensuring full compliance with obligations.

Even with clear answers to these questions, an adversary could still inflict damage or manipulate the international organizations tasked with overseeing the DMZ. For instance, Russia remains a member of the UN and has historically used institutions such as the Red Cross to advance its own interests.

Яскравим прикладом проблем з реалізацією є розмінування територій Боснії та Герцоговини, що триває десятиліттями. Дейтонські угоди зобов’язували сторони завершити виведення усіх своїх військ за лінію припинення вогню протягом 30 днів і встановлювали демілітаризовані зони для роз’єднання ворожих сторін завширшки 2 км по обидва боки від лінії припинення вогню.

A prominent example of the difficulties in implementation is the ongoing demining of territories in Bosnia and Herzegovina, which has persisted for decades. The Dayton Accords required parties to complete the withdrawal of all troops from the ceasefire line within 30 days and established demilitarized zones 2 km wide on each side of the line to separate hostile forces.

5. Prolonged Conflicts and “Frozen” Situations

Experience shows that demilitarized zones do not resolve the underlying causes of a conflict, nor do they necessarily lead to efforts to find a lasting solution. Instead, such arrangements often give rise to additional problems and can serve as a strategic advantage for the aggressor state. The longer territories remain outside effective control, the more entrenched the status quo becomes.

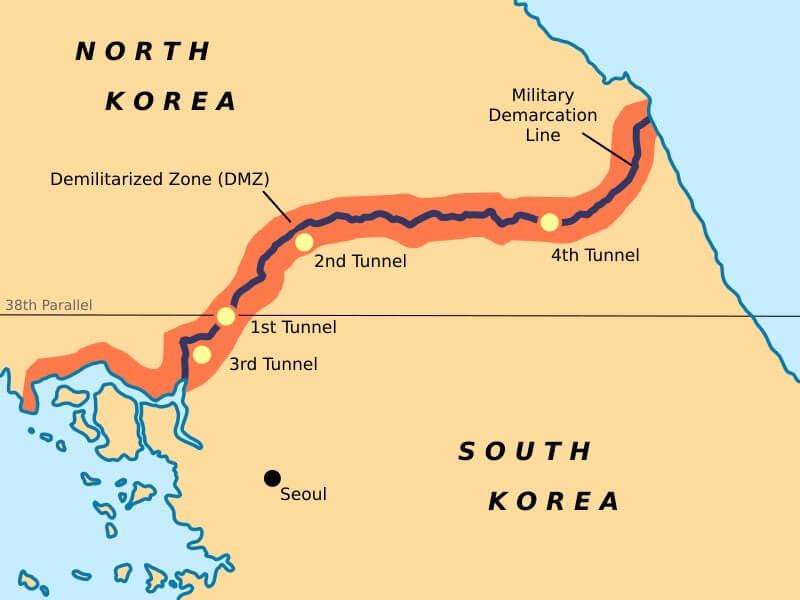

The Korean DMZ, for example, has existed for over 70 years, and recent developments demonstrate that temporary measures can become anything but temporary, offering little incentive to address the long-term fate of territories or states.

Another relevant example comes from Ukraine’s neighbors. In Transnistria, a buffer zone has existed since 1992, while the region itself has effectively remained in a state of “frozen conflict,” with any direct action limited to statements and diplomatic declarations.

Unlike autocratic leaders, Western politicians typically have only a few years to influence decisions. This short timeframe increases the likelihood of populist measures aimed at earning the “peacemaker” label or gaining political capital.

6. Impact on Civilians

The establishment of a demilitarized zone is often accompanied by the forced relocation of local populations, leading to both humanitarian challenges and the urgent need for security screening to ensure state safety.

The Korean DMZ provides a first example, where the local population was relocated, resulting in the loss of homes and livelihoods.

A second example is the post-1990s buffer zone in the Balkans. Although residents were not formally prohibited from returning to their homes, access was effectively blocked due to landmines and general military tensions in the area.

If a demilitarized zone is established in Ukraine, forced relocation of civilians may be required, at least along the frontlines. For those who remain within the DMZ, daily life would be severely complicated by damaged infrastructure and the direct threat of renewed Russian incursions. It is also important to consider individuals who have already been forced to abandon their property, as the creation of such zones would devalue their assets and result in significant losses of personal capital and livelihoods.

7. The Demilitarized Zone as a Tool of Propaganda

It should be noted that, like any other contested area, a demilitarized zone is likely to become a focal point for propaganda efforts.

In the Korean DMZ, North Korea actively employs both domestic and international propaganda, portraying South Korea as “preparing for war” to justify internal repression and external aggressive actions.

Based on previous years of hybrid warfare experience against Russia, it is likely that Russia would frame external propaganda around accusations of treaty violations, the establishment of biolabs, and similar claims to justify further aggression. Domestic propaganda would focus on militarizing the population and fostering hostility toward the West by emphasizing the “hardship” of newly acquired regions of Russia.

8. Geopolitical Context and Its Influence

Demilitarized zones are extremely sensitive and heavily influenced by the broader geopolitical environment due to the international nature of the agreements governing their creation.

The war in Nagorno-Karabakh demonstrates how the situation within and around a DMZ can become entirely dependent on global dynamics. The territory of the demilitarized zone has become a stage for regional actors who, pursuing their own interests, provide support to opposing sides of the conflict. A direct example of this is the involvement of Russia and Turkey, which have sought to strengthen their positions in the region amid limited Western engagement.

_The key lesson for Ukraine is that the demilitarized zone being proposed carries a high risk of turning Ukrainian territory into a battleground for global powers._Major actors have an incentive to prolong this “game” as long as possible, since it would influence broader international dynamics. It is therefore crucial to remember that the Ukrainian people would ultimately bear the cost of these geopolitical maneuvers.

9. Playing the Long Game and Conclusion

The final, but by no means least important, factor is the use of a demilitarized zone to prolong a conflict. This means that even with a “frozen” situation, the aggressor state can continue conducting covert hybrid warfare while gaining significantly more time to advance its narratives.

- The case of Abkhazia and South Ossetia is a striking example of this dynamic. After the conflict between Georgia and the separatists under Russian influence, a DMZ was established along the Inguri River under the auspices of the UN.

-

At the same time, Russia officially positioned itself as a “peacekeeper,” which allowed it to consolidate control over the effectively occupied territories, spread pro-Russian narratives throughout society, and, in 2008, formally recognize the “independence” of these regions. The demilitarized zone ceased to exist, but its socio-political consequences persisted within society and continue to resonate today, affecting the Georgian government.

-

Ukraine’s experience demonstrates that the state system remains vulnerable when it comes to providing comprehensive protection and countering all elements of hybrid aggression—aggression that the adversary has carried out almost since the founding of the country. Establishing a demilitarized zone in the occupied territories would only exacerbate the situation, prolonging the aggressor’s ability to exert destabilizing influence over Ukraine.

Author: Angry_ded